This is a question we might be asking ourselves as we try to get some sense of our place in this world. It is a question we may have been asking for a long time.

We can look at our current sense of this self and work on being clear about what that is. This sense of self has built up over time and has come to become the way we present to the world, which means how we present to other people. This ‘shell’ has been built up by experiences over our lifetime and built up by our interaction with other people. This includes those close to us; our parents, siblings, teachers and friends, but also those we come into contact with each day of our lives, however brief that interaction is. We learn to shy away from topics we find personally or mutually uncomfortable and build up an image of ourselves that we, currently at least, feel comfortable with and that we are sure will be acceptable to most of those we meet.

However, as we become involved with Buddhism and Triratna, the cracks in our carefully built facade begin to show. We may decide to become a mitra. (We have mitra ceremonies at the end of April, See Website). We may even start training for ordination. It is when we make those decisions and become serious about being a Buddhist and start looking more deeply at that original question of ‘Who am I’ that things can appear to go wrong and the ‘shell’ or facade no longer works.

Buddhism asks us to take responsibility for our actions. To be aware of the karmic consequences of how we have lived our lives and how we wish to live into the future. To take full responsibility for who we are is the bed-rock of our Buddhist practice. It is the basis of Buddhist ethics, the basis of the precepts, ethical training principles, which we often chant during rituals and explore in Mitra study.

Buddhism often talks about going beyond the notion of self but before we can do that we must be fully, really fully aware of who we are. We need to be aware of what it is that we are going beyond. If we don’t form this integrated sense of self then we run the real risk of just going beyond the bits that we are aware of, maybe just the nice bits that we admit to ourselves. Just the bits that are acceptable in polite society. So, we would form an alienated awareness about ourselves, some bits being very polished for public viewing and some bits very rough to be kept hidden.

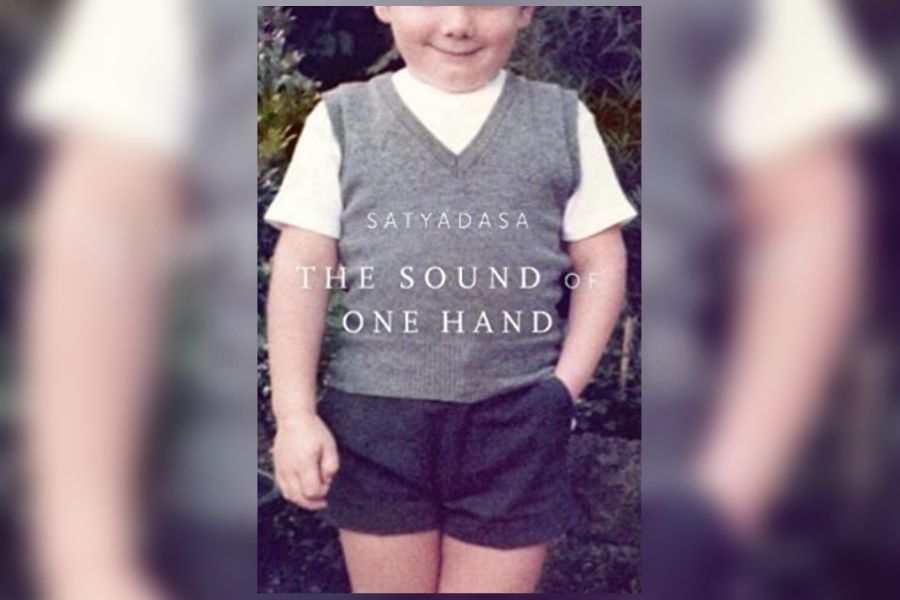

Recently Satyadasa came to the Centre on Friends Night to launch his new book, ‘The Sound of one Hand’. Satyadasa was born with one hand and his book, a memoir in style, very skilfully uses this disability to highlight his difficult personal journey from first engaging with Buddhism to eventually asking for ordination. Realising that he would have to face up to and take responsibility for his disability if he was to move forward on his spiritual journey. Satyadasa talked very engagingly at Friends Night about the need to take responsibility for all of ourselves, warts and all, to understand who we really are.

If you have asked for Ordination then I would suggest you read his book, we still have some copies at the Centre’s bookshop.

We all have a disability, none of us is perfect, whether that be in body or mind. We may have a nose that is too big, a serious illness or a mind that doesn’t do all the things that are expected. Whatever it is that we have that stops us from being perfect we must embrace and take responsibility for. Only in this way by accepting the whole of us, the real us, can we start to fully move forward towards a full understanding of reality, the beauty of imperfection.

I cannot walk on water or fly in the air, but it doesn’t stop me getting around. We are all capable of pursuing a spiritual life, of deepening our going for refuge. What stops us moving deeper is not accepting the whole of ourselves, using bits of us, of me, as an excuse for when things go wrong. What with blaming bits of myself and blaming other people it is a wonder anyone can move forward. We must recognise these traits in ourselves, these cherishing of, and holding onto excuses for why things are not going well or progressing as we might like.

When I looked at myself in detail at the start of my Buddhist journey, I realised that I have many disabilities, large and small. I, like many in our Sangha, am dyslexic. Reading or writing anything is very hard and tiring, sometimes impossible. But I have learnt to accept this limitation and work with it, using audio books and listening to Sangharakshita’s lectures, which actually gives more of the true meaning, the transmission that he is trying to impart to us.

An interesting exercise is to write down all the disabilities you have, both in the body and the mind. Take your time doing it, there will be some you won’t want to write on that piece of paper. This is who I am, this precious human body, this is what I have to carry me forward on my spiritual quest.

This work that we all need to do, in understanding who we are, is the first part of the Triratna system of practice, the stage of Integration. Without this basis of understanding, of who we are, we cannot hope to progress on our spiritual quest. Without this level of integration we will eventually crash into the wall of the limitations imposed upon ourselves because of who we naively think is the answer to the question of ‘Who am I’.

Taking responsibilities for our actions and facing both pleasant and conflicting situations with an open heart and mind is very important. We begin to realise that we have rigidly fixed our sense of ourselves. We think we know who we are, and are very unwilling to let go of that strongly held view. We eventually get to a breaking point where we have assumed that we are right and the rest of those around us are wrong. We have probably backed ourselves into a corner and are now trying to defend a position that we really do not need to defend. These difficult situations are how we can learn to really find out who we are. To really move to a deeper level of integration that does not rely on this dualistic approach to life’s experiences.

Satyadasa’s story ends well. He did learn to integrate his missing hand into his full experience of life, he did move forward in his quest for ordination and beyond. He now proudly wears his kesa and has re-envisioned himself, his whole-self with a new Buddhist name from his preceptor, Sadhu.

Finally, as I mentioned above, Satyadasa book and other good books are available in our bookshop. Please remember that the Centre bookshop is very much an ethical way of spending your money. The profits from the bookshop support the Ipswich Centre, support Triratna’s Windhorse Publications and also support the authors directly. None of this occurs if you buy from one of the large online retailers who can offer you a few pence discount. Even small actions can make a big difference, and redefine the type of person you are and maybe wish to become.

Have a good month.

Bodhivamsa

May 2022